Compound Monty.

Weekly constraint.

This week we had to combine two different principles that focused on numbers, relationships, and probabilities. I decided to use the Monty Hall problem and Compound interest. I picked the Monty Hall because the problem interests me in how it deals with probabilities and how people view it. I wanted to see how it could be incorporated into game design. Once I had decided on making the Monty Hall problem the main game mechanic, Compound Interest was a natural fit to build up the rewards.

What is it?

Compound Monty is a card game for two players. One player takes the role of a contestant on a game show, the other plays the host. It combines the Monty Hall problem and Compound Interest together. The more you guess right the larger your prize. But be warned guess incorrectly and lose it all. With added luck cards to spice things up, how much will you risk, to win it all.

What tools were used?

- Paper: Used to make the card game.

- Microsoft Publisher: To make the manual.

- Adobe Photoshop: Used to design the cards and box

Prototype

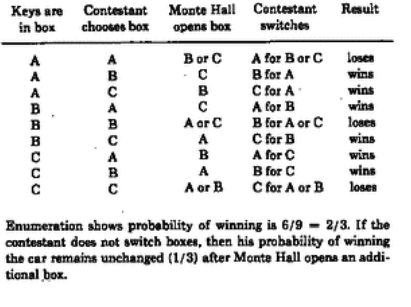

What is the Monty Hall problem? There are three boxes, one contains a prize the others are empty. The player picks a box, then one of the unpicked empty boxes is opened. The player is then offered the chance to switch boxes. Mathematically it is always in the players best interest to swap as it gives a much higher chance of winning. Selvin (1975) showed the probability of winning if the player switches are 2/3 compared to 1/3 if they stick.

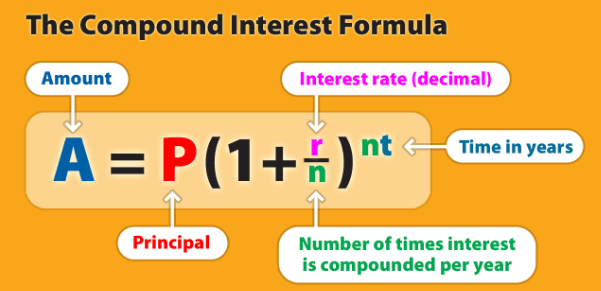

Knowing that Monty Hall is normally shown as a game show I played into this by making the prize in the box a cash sum. It was simple to add in multiple rounds of the player picking a box (if they won the previous round.) and increasing the cash prize each time. I used compound interest to calculate the amounts the player could win each round. Compound interest is calculated using the formula:

I set my principal amount as £100, my interest rate (r) at 100%, the Time (t) was set to ten years, and the number of times the interest is compounded (n) was twelve. I then picked every yearly result as I wanted the prize amount to grow quickly. Below are the first five cash prizes.

After some playtesting I found that players were more than willing to keep playing to try to win larger amounts. However, no one made it further than winning £4,662, and the few that did changed their strategy from always switching to sticking as they felt that they had been right four times so they must have picked the right door this time, this is known as the gambler’s fallacy. Hertel (2015) studied risk v reward in games. He investigated probabilistic reasoning and how players understand randomness. He uses the example of a coin being flipped six times with the results being THTTTT. What will be the outcome of the next flip? He points out that players tend to focus on past results and would likely predict that the next outcome would be heads. Because of this I added the luck cards to give the player a better chance of progressing further. It is important to balance the luck cards to ensure that the game was still fun. Because of this I settled for a 70/30 split between good and bad cards. One further iteration was made where the player could keep one good luck card and play it when they felt it was in their best interest to do so.

References

Adobe Inc (2022) Adobe Photoshop [Application] Microsoft Windows.

Hertel, J.T., 2015. Understanding risk through board games. The Mathematics Enthusiast, 12(1), pp.38-54.

Microsoft Corporation (2022) Microsoft Publisher [Application] Microsoft Windows.

Selvin, S., 1975. A problem in probability. The American Statistician, 29(1).

The Calculator Site. (n.d.). Compound Interest Formula – How to Calculate Compound Interest. [online] Available at: https://www.thecalculatorsite.com/finance/calculators/compound-interest-formula.